Local Air Quality? Click here.

PREFACE

Why did I do this written exercise: I wrote this article over the last 2 months (February-April 2025). It’s a passion project and its purpose was to help me focus and decode my chess resources. I now have the time and mental calmness to devote to this fascinating board game. I enjoy the tactile feel of the board and well-balanced pieces. I’m using the pedagogy I used from the high school classroom, seeing if it can help me in my post-teaching lifestyle. Why am I posting it online: I want to pay it forward. When I started messing around with chess in 2002-2003, I was welcomed to it by my local Toronto chess store. I never forgot those interactions. I want to add supportive, light-hearted content to the internet. Limitations and kind warnings: My posts are not peer-reviewed nor vetted by FIDE ranked chess writers. I’m assuming readers will do their own due diligence (so they don’t get laughed out of [or disqualified at] the next competitive chess club events).

LOGICAL CHESS, MOVE BY MOVE

About the book. About me.

…Every Move Explained. Irving Chernev. 2004 New Algebraic Edition. Originally published in 1957 by Faber & Faber (UK). 1998 BT Batsford. Reprinted 2000, 2001, 2002, 2004. PT Batsford, The Chysalis Building, Bramley Road, London. An imprint of Chrysalis Book Group plc. ISBN 0 7134 8464 0

I still remember having the dude at Strategy games pick this book out for me. He liked the author’s ability to explain tough concepts in a conversational style. He also sold me Winning Chess Tactics for Juniors, edited by Lou Hays. He assured me not to get turned off by the slim book’s title. “For juniors” doesn’t mean it’s meant for children — far from it. It gives me puzzles I can use for recognizing “mate in 2” or “draw in 4”. I didn’t realize Irving Chernev was alive from 1900-1981, and that this book was in its 6th reprinting. Yes, it’s that popular! I paid $34 for it in 2005. Has it really been 20 years since I picked up this book and went at it?! Nice.

1 Human playing against dozens of players.

How the fuck do they do that? What we know for certain, is that the human-master isn’t going through each board and memorizing winning moves. They simply don’t have the time to do that! Irving Chernev (IC) believes it’s the chess-master’s ability to play positional chess.

POSITIONAL PLAY.

This mindset prevents chess players from embarking on rash attacks and premature combinations during a chess game. It guides the player to develop pieces so that they are at their strongest, they occupy the most territory, and cramps and harasses the enemy. With practice, the player will recognize combinations as they appear on the board.

combinations.

What is a chess combination? IC has this 1960 definition (link). I went to IC’s 1960 book and read the primary source (page 14): what is a combination? “A combination is a blend of ideas — pins, forks, discovered checks, double attacks… [they] endow the pieces with magical powers. It is a series of staggering blows before the knockout. It is the climatic scene in the the play appearing on the board. Its is the touch of enchantment that gives life to inanimate pieces. It is all this, and more — a combination is the heart of chess“.

IC reminds players to developing ones’ pieces before starting combinations (pg. 15).

the kingside attack. page 9.

When do I start a king-side attack? Be it playing as white or black? ANSWER = look at the other side’s kings’ position. Are there 3 pawns, a knight, a rook, and a castled-00 king in position? That king is well protected. “The moment the formation is changed, the structure is loosened and weakened. It is then vulnerable to attack“.

If the opponent isn’t breaking their pawn, rook, or knight structure, then the human-master “induces or compels by various threats the advance of the h-pawns or the g-pawn… Once either pawn makes a move, it creates a weakness in the defensive structure which can be exploited“.

GaMe 1.

“What happens when h2-h3 is moved to prevent a pin” (pg. 11). This game was played in 1907 in Berlin, Germany. Giuoco Piano. von Scheve against Teichmann. White versus black.

The Giuoco Piano is also called the Italian game, the Italian Opening, and Piano Opening. In my big blue book (Modern Chess Openings, 15th edition [MCO-15], by Nick de Firmian [2008, McKay Chess Library, Random House]), it’s described on pages 18-19, with variations described until page 25. In the ECO (the Encyclopedia of Chess Openings) it’s called C50 to C54.

“The objective of all chess openings is to get one’s pieces out quickly”(pg. 11). That makes sense to me. I want to attack and get ownership of the centre squares d4, e4, d5 and e5 and then develop my knights, bishops and queen. My two rooks are developed mid-game.

“Black must fight for an equal share of the good squares. Black must dispute possession of the centre”. Here’s IC’s reason: “pieces placed in the centre enjoy the greatest freedom of action and have the widest scope for their attacking powers”. IC uses knights as an example. It’s also hinted at not cramming knights in the corners or the sides. I’d also use that mindset with my bishops. They can attack diagonals right across the board. “Occupation of the centre means control of the most valuable territory. Occupation of the centre, or control of it from a distance, sets up a barrier that divides the opponents forces… It leaves less room for the [opponent’s] pieces, and makes defence difficult, as [their] pieces tend to get in each other’s way“. All my coaching books warn against crowded play — avoid bunching up pieces (unless I’m using 2 rooks in one file to bolster each other).

“Develop knights before bishops!… bring out your knights before developing bishops!” IC repeats this twice on page 12, and that rings true with other coaching books I’ve read. The reasoning makes sense to me: knights are best played at the beginning of the game, as their movement is in short bursts. Bishops can control diagonals across the board and IC believes it might be difficult where to place them (when compared to knights). Bishops can be used to pin an enemy piece or control long stretches with a single move.

IC wants the reader to protect pawns early in the game. He’s not a fan of sacrificing them for no reason. IC, like other chess-masters, let lower value pieces protect their peers. If a knight can do the protection instead of activating one’s queen, do it. Curiously, IC likes putting pieces to work instead of pawns. This might contradict pawn structure taught by other humans — or not. IC implies that once a piece is placed, move on to developing other pieces on the board — 2 knights + 2 bishops + 1 queen. Then rooks. Somewhere in that piece development, spend a move castling my king to get it behind a pawn & rook shield. Annoyingly, IC contradicts himself by espousing “2 golden rules for opening play: [i] place each piece as quickly as possible on the square where it is most effective. [ii] Move each piece only once in the opening” (pg. 14). IC isn’t a fan of putting pawns on squares meant for the knights in the game’s opening.

IC noted that the pawns surrounding the kings are valuable — to the point where a pawn-bishop sacrifice might be worth it, if it king’s safety is jeopardized. If one attacks these pawns (d2, e2, f2 for white and d7, e7, f7 for black), then it can lead to the opponent’s king being driven out and exposed to attack.

IC wants the reader to appreciate the concept of maximum piece mobility. For example: bishops can control and attack across board-wide diagonals. IC would move bishops as far forward as possible, so that they can control the centre (d4, d5, e5, e4) and harass the opponents back ranks (horizontal [files are vertical]).

IC has a playing preference. At the games’ beginning, knights are best played at c6, a6(?), f6, h6(?) for black and/or c3, b3(?), f3, h3(?) for white. He doesn’t like putting a pawn in its place.

IC cautions the reader about doing mechanical, mindless piece development. If a pawn has to be moved before other pieces (i.e., it provides black a retreat for her bishop), move the pawn! “Development is not meant to be routine or automatic; threats must always be countered first” (pg. 15).

What’s a “coffee house chess move”? I checked out chess.com and lichess.org forums. If one’s called a coffeehouse chess player, it’s an insult. Coffeehouse players use aggressive opening moves, set traps for their opponent, and ignore positional play (piece development).

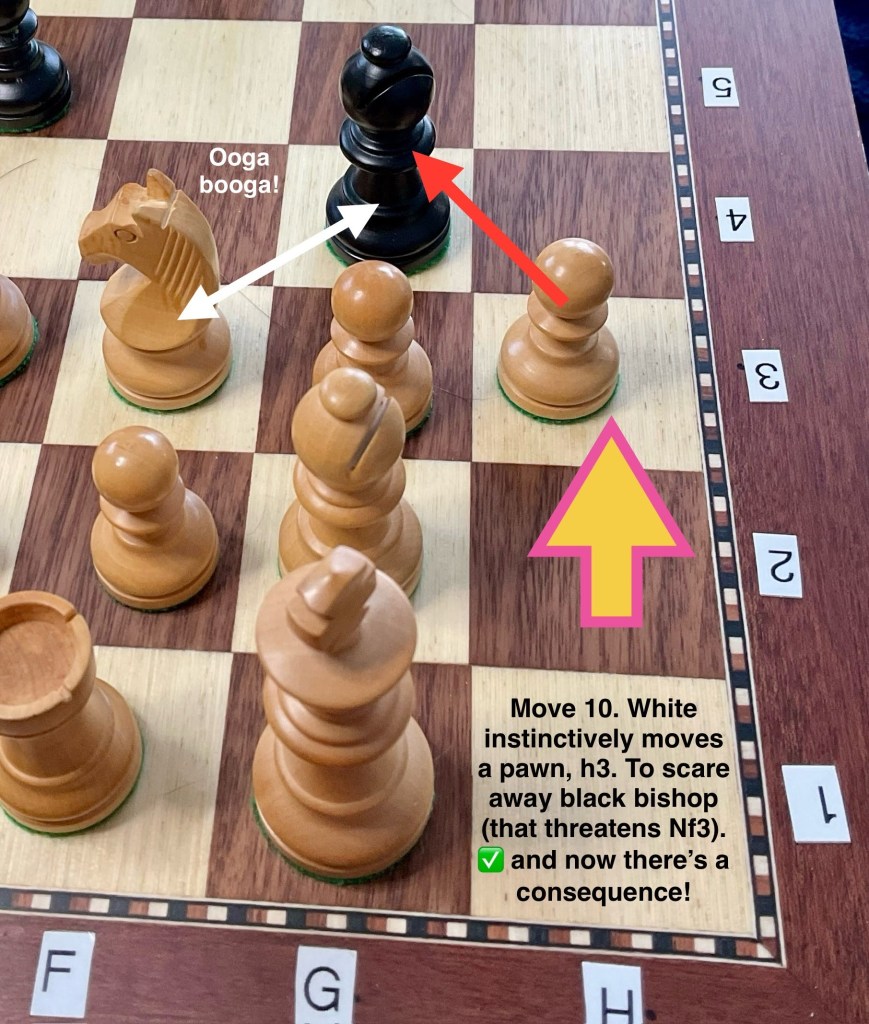

Don’t jeopardize my king’s pawn structure until I have to. “Playing h3 or g3 [or in the case of black, g7 or h7] after castling creates an organic weakness that can never be remedied”. He’s right — pawns can only move forward and never retreat. “You should never, unless of necessity or to gain an advantage, move the pawns in front of the castled king… [Alekhine often said] Always try to keep the three pawns in front of your castled king on the original squares as long as possible”.

“Develop with a threat whenever possible” (pg. 16). “Open lines are to the advantage of the player whose development is superior”. What are open lines? IC reminds the reader that knights are the most mobile at the board’s centre — edges (ranks 1 & 8, files a & h) cramp their style! “A knight at f3 [f6 for black] is the best defence of a castled position on the kingside” (co-quoted by IC, pg. 17).

IC likes replacing a piece with another of equal or stronger value. I think he like the idea of keeping pressure upon the centre squares (meaning d4, d5, e4, e5). In this game’s case, a black knight was lost but its spot was replaced by their black queen. Queens can dominate the board’s centre and bears down (in this game’s case) on a hapless white e-pawn. White is now in a right pickle (be in a right pickle.[n.d.] Farlex Dictionary of Idioms. [2015]. Retrieved February 28 2025 from https://idioms.thefreedictionary.com /be+in+a+ right+pickle ). How do they solve the problems posed by the position of the menacing queen and attacks on stranded pawns? White can’t move a pawn up and scare off black’s queen — it’s an illegal move (i.e., one can’t move a piece that puts themselves into check).

“Positional judgment“ (pg. 13). I can’t figure out what IC is getting at with this phrase. It might have something to do with not wasting time on the board. Develop a piece and then leave it alone. Example: once I move Nb to either a3 or c3, don’t move it again on my next move! That’s wasting time. IC cautions me “that his and other maxims are not to be blindly followed. In chess, as in life, rules must often be swept aside”. If my opponent makes a blunder, attack.

Book report informal meta-summary: Before I move on to the next game, I want to remind myself why IC annotated this game. It had a player set traps and play aggressively BEFORE developing all of their pieces. At the first sign of a pin, the same opponent broke up their king’s pawn structure and ultimately lost the game. Game 1 illustrated king-side attacks.

game 2.

What happens when h2-h3 is moved to prevent a pin. Another response! This game was played in 1928 in Liege, Germany. Giuoco Piano. Liubarski versus Soultanbeieff. White versus black.

There can be more than 1 good opening move! Chess masters advocate the following maxims: get [my] pieces out fast! Move each piece only once in the opening*. Develop with a view to control of the centre. Move only those pawns that fascinate the development of pieces. Move pieces, not pawns! (pg. 19). I’ve run across several authors who caution against using pawns as canon fodder. Yes, pawns and pieces can be sacrificed FOR A REASON. I need to be mindful of how I treat my knights, as I find them hard to control. And I’ve caught myself wanting to send them on suicidal rampages all over the board.

Here’s an example where mechanical chess playing can backfire: IC warns the reader against moving a piece twice in a row, as it’s a waste of time (at the beginning of the game). That’s true… except when the opponent throws a threat down that cannot be ignored. “Threats must be parried before continuing development” (pg. 20).

I’M UNCERTAIN: At what point does the game opening end, and the mid-game begins? I think it’s when as many pieces (not pawns) have been moved to their most mobile spot.

“All chess theorists [at least the ones outlined by IC] affirm the validity of the concept of leaving the kng-side pawns unmoved, from Staunton,… it is seldom prudent in an inexperienced player to advance the pawns on the side on which his king has castled, to Reubin Fine… the most essential consideration is that the king must not be subject to attack. [The king] is safest when the [3] pawns are on their original squares”. (pg. 21).

This game has a moment where black DOES break apart their pawn structure in front of the king. Why would black do such a seemingly passive move? Black’s responding to white’s decision to break up white’s kingside pawn structure — with an attack. IC notes that black did NOT castle. Black is forgoing a kingside castle and going after white’s weakened pawn screen around the king.

“Do not grab pawns at the expense of development or position” (pg. 22).

*Double-moved pieces are used in tournaments with success! I’ve been skimming ahead to a 21st century chess writer, John Nunn. This UK master delves into modern (hypermodern?) chess strategies. I’ll read Understanding Chess, Move By Move. John Nunn. Gambit Publications Ltd. England. 2001, 2002, 2004, 2005. http://www.gambitbooks.com

game 3.

What happens when h7-h6 is forced. White’s response. This game was played in 1929 in Gand-Terneuzen, Belgium. Colle System. Colle versus Delvaux.

Question: Why would a player bunch up their knights close together and limit the movement of their bishop and queen? Answer: Closely positioned knights can add pressure to the centre squares (e4, d4, e5, d5). This sortie respects the rule of mobilizing as many pieces as possible. Get pieces out of the back rank (for white, that’s row 1, for black, that’s row 8).

IC can’t stress enough the value of keeping pressure on the opponent’s centre squares (in white’s case, that d4 & e4 and for black, d5 & e5). “Counterplay in the centre is the best means of opposing a kingside attack and to secure counterplay, the pawn position must be kept fluid” (pg. 25). I think I need to be a bit forgiving with IC’s word choice — fluid pawn positions?! Pawns can’t move backwards nor side-to-side. A better way to say this is pawn position must remain near the centre action, ready to apply pressure. Don’t push pawns too far ahead where they get stranded and ultimately picked off.

Game 4. White sacrifices a bishop to remove black’s h-pawn. Nah.

game 5.

This game illustrates the danger of castling prematurely and ignoring the board’s centre. Before I decode and digest game #5: When I play chess, I find myself castling as soon as possible — usually withing the first 5 or 6 moves. I might be ignoring the centre squares, or else I shut the game down whenever the computer-opponent gets uppity. I don’t like conflict, even with inanimate objects which is what the computer engine really is. It’s not alive nor sentient. It’s a network of algorithms — with subroutines built in to force blunders and bizarre play. I just can’t tolerate playing against other humans who act like trolls either IRK or online. Perhaps the latest AI kick will make computer chess more pleasant and quirky for me. I can dial up or dial down the snark as my mood changes.

“It is good strategy to make developing moves that embody threats as it cuts down the choice of reply [by my opponent]” (pg. 35). In the first 1-3 moves! Example: if I have a choice between moving a piece that threatens my opponent’s’ piece OR use a piece to protect my piece, try to attack. I don’t have to be a passive player. In the same vein, it’s okay to sacrifice a piece if it draws the king out from his pawn-bishop-knight-rook shield. The point of chess is to capture the king. Example: if I lose my bishop but force my opponent to capture it with their king, well… I’m launching an attack!

“In the opening, a bishop is best placed for attack when it controls a diagonal passing through the centre or when it pins a hostile knight and renders it immobile” (pg. 35). I can’t tell whether IC believes this advice or not. In the next sentence, he also recommends another option — move the bishop just enough to control diagonals, at the risk of hemming in one’s undeveloped queen.

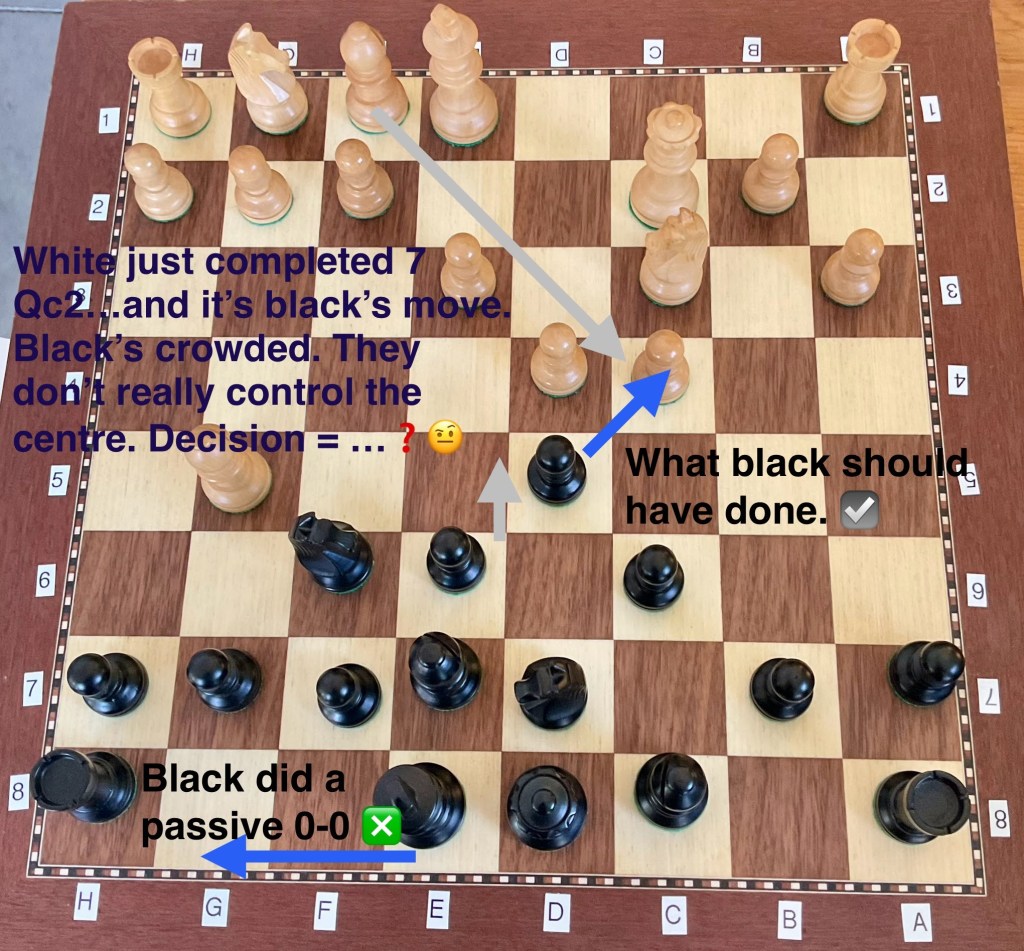

I love to castle early, but it can backfire on me. I’m a timid chess player, especially if I’m playing against another human. Somehow, I have to learn that computer chess has NO feelings. I can be as aggressive as I like against the machine. It doesn’t care and won’t hold a grudge. “Chess is not for timid souls, wrote Steinitz in a letter to Bachmann. Castling early in the games is generally sound strategy. In this case it is inappropriate, as white’s centre is formidable and best be destroyed”. Wrestle control of the centre board, then promote king safety. Take my chances “of surviving whatever attack might follow. It cannot be worse than this passive castling…” IC even doubles down on this rule(?): castle because [I] want to or because [I] must, but not because [I] can. In game #5, black castled too early and didn’t contest the centre squares. White dominates d4, d5, e4 and even e5! If I were white, I would then castle to get some king protection. IC would disagree with me. He’s all about attack, attack, ATTACK. Don’t give black develop other pieces. Kill! Kill! Fuck.

In game #5, black resigned before it could become checkmate. How do I feel about not castling at the first opportunity? If I’m putting some degree of pressure on the centre squares, that’s adequate for me. I’m still biased towards king-safety and go 0-0 or 0-0-0. Meh, it’s an interesting suggestion. I’ll consider it.

Game 6.

This games another example of castling at the wrong time and ignoring the importance of controlling the board’s centre.

When I play white, move-2 Nf3 is a powerful piece placement: “(i) the knight develops in 1 move to its most suitable square in the opening; (ii) it exerts pressure on 2 of the 4 squares in the vital central area [e5, d4]; (iii) it comes towards the centre so that it enjoys maximum mobility; (iv) [Nf3] helps clear [white’s] king-side, enabling early castling of the king on that side; (v) it is posted ideally for the defence of the king after [they] castles; and, (vi) it comes into play with a gain of time — an attack of [black’s] pawn”. (pg. 39)

In game #6, white sends their bishop shooting across the board to Bb5. Black responds (after dealing with centre-square threats) with moving a pawn instead of developing a piece. Normally, pieces (like knights) are developed before pawns. Black hasn’t done that. In fact, black has broken up their pawn structure protecting their kings. Why the pawn push? IC’s answer: “(a) black must drive off [white’s] bishop before [they] can advance [their] d-pawn (otherwise the [black] king is in check); (b) the time lost in moving the pawn is compensated for the the fact that the bishop must also lose a move in retreating; (c) [black] opens a fine diagonal for [their] queen; and, (d) the attack on the bishop will win a pawn, and ‘a pawn is worth a little trouble’ according to Steinitz”. (pg. 41) I agree with (a), (b) and (c). (d) is a bit too glib for me.

By move 8, white decides to send his king behind the wall of pawns. And IC call that’s a poor decision. Take a look at the image. I think IC has a problem with how little white is contesting the centre squares. The bishop and knight can be chased off by the invading black queen. IC would urge queen-side piece development and then 0-0-0 (that’ll require Qd1 and Bc1 to get developed).

By move 11, black developed his bishop into a mating threat.

By move 12, black swung their queen-side bishop across the board and is now inhabiting g4, with protection a nearby black knight. Black has penetrated white’s king-defence and cannot be quickly driven off by pawns (BTW, if I’m looking at the nearby image, white’s g2 was moved up to g3). White’s king-side, castled, pawn shield now has holes in it — it’s weakened and ripe for black-piece attacks! Black’s bishop, knight, and black’s queen went in for the kill.

Games 7, 8, and 9. Meh, I’ll pass.

Game 10.

IC claims game #10 is an example of a player playing mechanical chess. What the fuck does that mean? Unthinking? Following the rules? Ignoring rules? What gives! I’m getting conflicting messages from Irving Chernev (and his estate).

At move 12, white captures black’s pawn, en passant. So, exf6. It’s one of those rare times a pawn can capture an opponent’s pawn beside it. En passant was developed sometime after the 2-square pawn move was introduced between the 13-16th centuries (to speed the game up). It’s properly described in the FIDE chess laws: Article 3.7.4.1 URL is https://handbook.fide.com/chapter/E012018 .

By game #10, IC labelled specific patterns with the following names:

- French Defence.

- Ruy Lopez.

- Colle System. Colle attack.

- Giuoco Piano.

- King’s Gambit, Declined. I’ll have to remind myself of their importance and why they are used so often. Is it bad chess when players do their own variations of those patterns?

Game 11.

This game illustrates a player methodically chipping away at the king’s guards... harassing the guards (R,P,N) until they are impelled to move. IC reminds the reader that there are no 100% guaranteed development strategies in the openings. If I’m playing against a human, there will always be some randomness involved.

José Raúl Capablanca believed in fast piece and sound piece development. IC details it as the following:

- (a) begin with 1 e4 or 1 d4, either of which moves releases 2 pieces;

- (b) anchor at least 1 pawn in the centre and give it solid support. Pawns in the centre keep enemy pieces from settling themselves on the best squares;

- (c) where feasible, bring out [my] knights before the bishops;

- (d) knights can defend and attack best at f3 & c3 [for black, f6 & c6];

- (e) of 2 developing moves, select thee more aggressive one. Develop with a threat if [I] can;

- (f) move each piece only once in the opening. [IC goes on to emphasize placing] it at once on a square where its has some bearing on the centre…;

- (g) move at most 2 pawns in the early stages of the game. Play with pieces;

- (h) develop the pieces with a view to controlling the centre, either by occupying it or bearing down on it from a distance, as fianchettoed bishops do;

- (i) develop the queen, but close to the home to avoid her being harassed by pawns and minor pieces;

- (i) do not chase after pawns at the expense of development; and,

- (j) secure the king’s safety by early castling, preferably on the king-side. I’d like to add a clarification with (j). Don’t castle if the centre board’s dominated by my opponent — counterattack!

Game #11 used the Colle attack, and Queen’s gambit. 2 black bishops and 1 black knight punch through pawn shield. Black nailed white, 0-1.

Game 12.

This game has black chipping away at white’s king-guards. It was played in 1934 in Liebwerda, Germany between Rudolf Pitshchak (who played Bobby Fischer in 1957) and Salo Flohr (a Soviet GM known for patient, positional chess). What the hell is the English opening?!

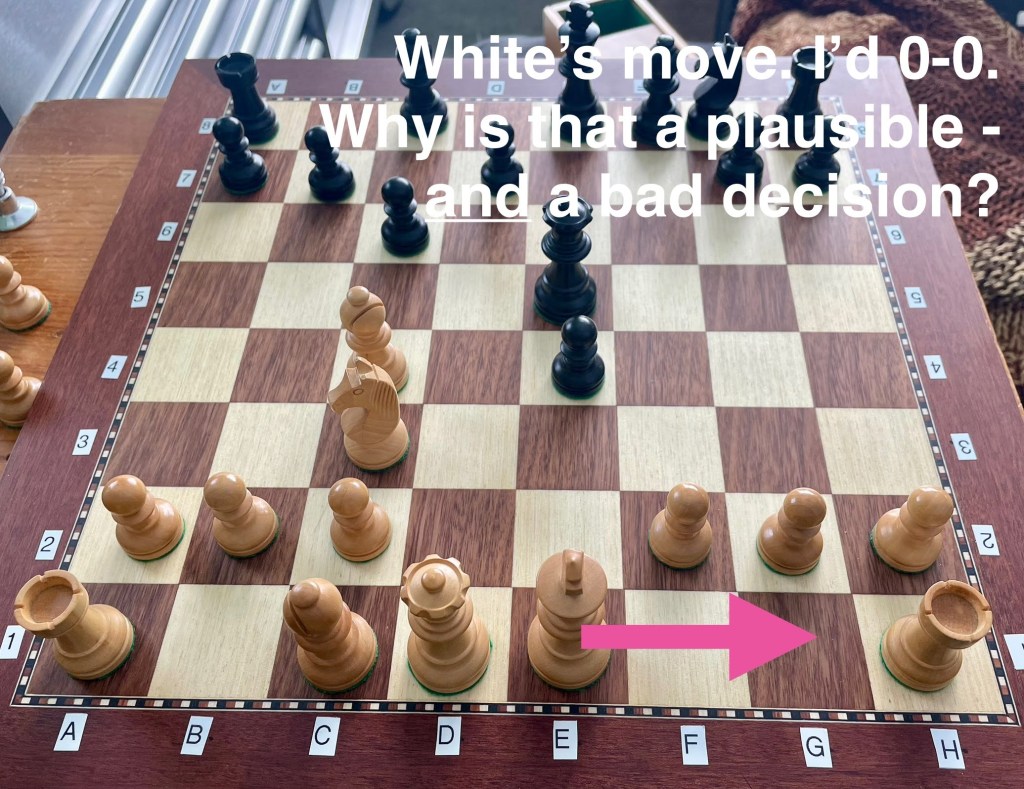

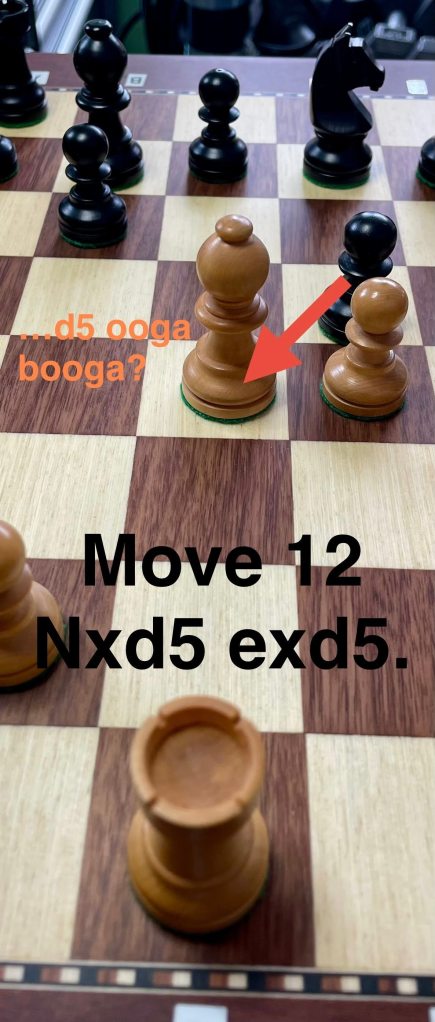

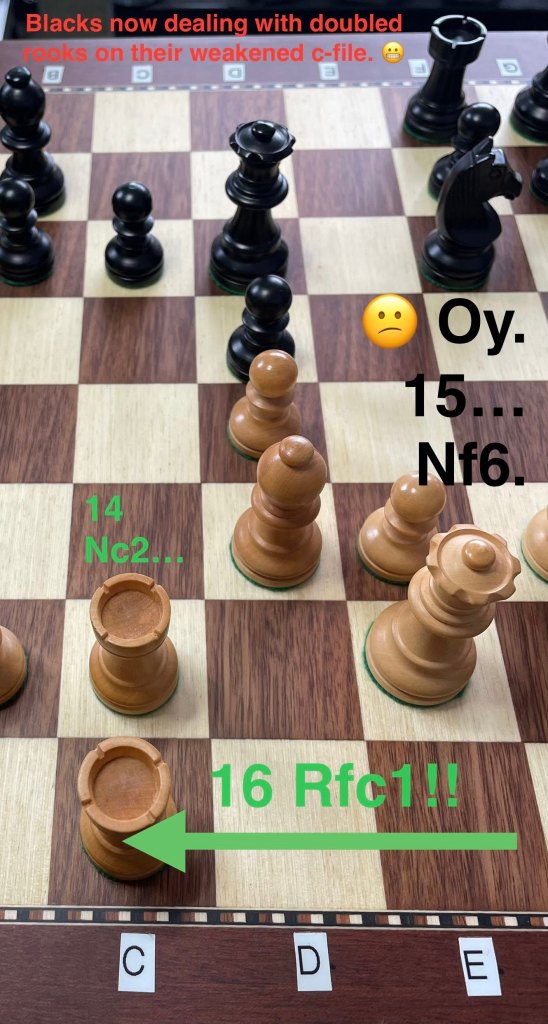

Black develops their queen-side bishop and has it careen across the diagonal to g4, threatening white’s Nf3. White has to decide what to do by move #10. They decide to push a pawn up to force black to declare their black bishop’s intensions: attack a nearby white knight? I can understand white’s decision (chase black Bg4 off), however, white now has a weakened pawn structure!

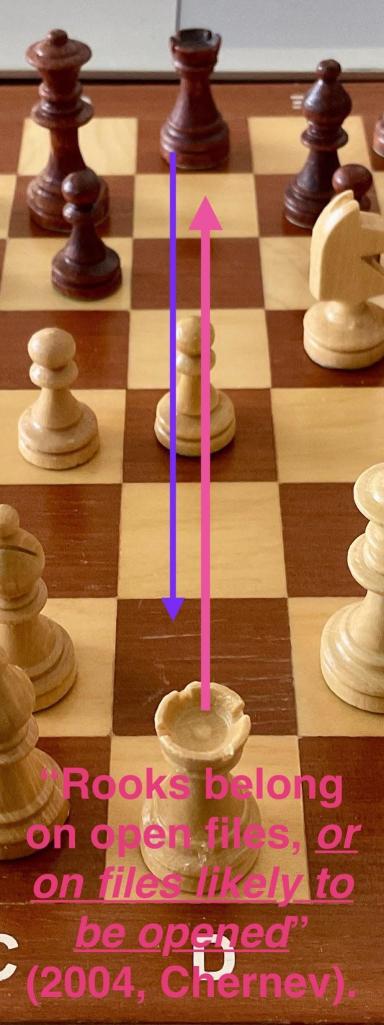

IC’s interesting comment by move #11: if my king’s pawn structure is weakened and my opponent’s pieces are streaming forward for the kill , “action in the centre is the best remedy against a king-side attack” (pg. 73). When I develop (i.e., move it from d1 or d8) even by 1 step, it can dominate files and diagonals. “Development of the queen serves another purpose in that the first rank is cleared for the rooks. [The rooks] can now switch over towards the centre and get control of the most important files” (pg. 73). I’m assuming those important files are d, e, and f for white and black.

So, by game 12, I’m introduced to the English Opening. Add this to the growing list of systems and/or openings:

- The English Opening.

- French Defence.

- Ruy Lopez.

- Colle System. Colle attack.

- Giuoco Piano.

- King’s Gambit, Declined.

Game 13. This game illustrates black’s g- and h-pawns under attack. Meh, I pass.

game 14.

In this game, black’s f6-knight gets smoked and also uproots black’s g-pawn. Pay attention to white’s quiet pawn move later in the game! Game 14 was played in 1916, Berlin Germany against Siegbert Tarrasch (he disliked cramped positions) and Jacques Mieses (one of the first IGM designations by FIDE in 1950).

What is zwischenzug? Zwischenzug is a German word that means “in-between move.” Such moves are common in chess, but many times they can be quite unexpected! Other terms which mean the same thing in chess literature are intermezzo, intermediate move, and in-between move (“What Is Zwischenzug?” Online. CHESS.com, updated April 30, 2018. Accessed March 13/25 @ 1651 EST, https://www.chess.com/ article/view/ zwischenzug-chess).

Game 15. Irving Chernev includes Games 15 and 16 because they illustrate what can happen if one doesn’t protect ones’ king adequately. Game 15 has Alexander Alekhine do some unconventional attacks on his opponent. IC also claims that Alekhine punished black for wasting time-play. Remember, this is high-level chess where the players are ruthless towards each other. Friendly play, it ain’t. Meh, I pass.

Game 16. Here’s another game that gets a disparaging description from IC. Irvine claims the game illustrates plausible but perfunctory chess play being harshly treated (by the opponent). Meh, I pass on this heavily annotated game.

the queen’s pawn opening. page 100.

Pre-reading 1. What’s the Queen’s Gambit declined? This system is added to the existing list: Queen’s Gambit declined; The English Opening; French Defence; Ruy Lopez; Colle System, Colle attack; Giuoco Piano; King’s Gambit Declined; The Pillsbury Attack; and, “an early fianchetto of a bishop”.

Pre-reading 2. The queen’s pawn opening requires free movement of the piece. In game 3, black moved c7 and later d7 in the opening. “This freeing move of the[white’s] c-pawn is the greatest importance in queen’s pawn openings” (pg. 24). I’ll need more explanation to appreciate this passage earlier in the book. Is IC referring to white AND black’s pawns about the queens? So, c2, d2, e2 and c7, d7 and e7?

IC is quite content with ignoring generalizations if unexpected threats show themselves. “Move only 1 or 2 pawns in the opening!” says all the [experts], but no principle must be followed uncompromisingly” (pg. 24). This adage is repeated throughout IC’s book. Do THIS and THAT. Except when you shouldn’t. Pay attention to the play. Develop pieces yes. But don’t let the opponent threaten without a response (parry threats before continuing development).

Move 1: d4 d5. Move 2: c4…

Okay, so what is the Queen’s Pawn Opening? Remember, the King’s Pawn opening is 1.e4, and that can lead to rapid development and a whole bunch of mobility. I’m also fighting to exert control of the centre squares (d4, d5, e4, e5). If my first white move is 1.d4, then I’m committing to Queen’s pawn games. According to IC, Queen’s pawn openings are all about applying pressure to the c-file.

Game 17.

This 1895 game was played in Hastings, England. This was a battle between Harry Pillsbury (who played white [a US citizen who upset reigning world champion Emanuel Lasker]) and James Mason (playing black [an Irish-American player who became one of the world’s best 1/2 dozen players in the 1880s]). It’s a classic example of white controlling the c-file, while black FAILS to free them-self by …c5

IC describes 4 strengths of the Queen’s pawn opening:

- The d-pawn occupies an important square in the centre and attacks 2 valuable points, e5 and c5.

- Control of these squares keeps the opponent from making use of them for their pieces

- The queen and dark-squared bishop can now leave the first rank.

- The king is safe from some of the surprise attacks that occur in king’s pawn openings. (Pg. 101).

When 1. d4… d5, black’s equalizing the pressure. It prevents white from continuing with 2 e4, and all the drama that extends from that development. If I assume black replied with …d5, then white plays 2 c4. That’s an offer (a Queen’s Gambit?). IC believes the reason for “playing 2 c4 so soon is that it disputes the centre at once, without endangering the safety of the king… There’s also another purpose [for white] — a strategic one”. (pg. 101) Apparently, ownership of the c-file is very important for executing the Queen’s Gambit.

According to IC, white posts their queen at c2 and develops white’s queen-rook at c1. If maintained, this queen-rook structure MIGHT be enough to paralyze black’s piece movement (I’m sure there are anti-Gambit strategies developed to foil it). Question: are these gambits also found on black pieces? If so, what are they called. By the above definitions, I’d assume Queen’s Gambits can only be initiated by white. Black decides how the gambit’s received.

If black decides to take that c4 (so, 2…dxc4), black loses control of the board’s centre. Interestingly, IC considers 2…Nf6 a weak option. Yes, black’s knight will protect their d5 pawn; however, however, the knight can be driven away and waste black’s time. Furthermore, a thoughtful white player will be able to continue dominating the centre squares (by driving black knights and queens away from that hotly contested piece of real estate).

Answer: there must be resources out in the wild about black counterattacks. Black deserves a better fate, yes? Yes. Black is Okay!** Black must respond with 2… e6, thus using pawn structure to support other pawns. It allows black’s pieces to develop elsewhere.

IC recommends putting up a black pawn fight for the centre before developing black’s c-bishop (move 5 was 5…b6 in hopes of developing a black bishop). Apparently, black now has better defences against the Pillsbury Attack (go after white’s pawn, 5… dxc4).

**My initial attempts at decoding the Black Is Okay series — the Hungarian author has a very idiomatic writing style that won’t mesh well with Canadian-English writers like me. Some of his comments are cringe-worthy and bigoted. I suspect he was a charismatic, European chess player that he got a lucrative book deal. When I end up decoding his book, I’ll have to separate the chess player from the man. PN.

If the point of Queen-side openings is to apply pressure to the c-file, then white’s move 7 Rc1… enhances white’s control of that entire file. Once the pieces and pawns move out of the way (or are captured), white’s rook will drill right into black’s 8th rank. Black is also advancing and challenging white’s pieces on the c-file. According to IC, black needs to allow their c7 pawn to advance and challenge the centre. Don’t push a knight into that role (instead of Nbc6?, go Nbd7!).

Surprisingly, game #17 is still in its opening phase at move 10, according to IC.

By move 16, white has doubled up their rooks on the c-file. Black is now in a world of trouble. “The device of doubling rooks on their open file more than doubles their strength on that file” (pg107). IC recommends players who are playing black, and witness major pieces piling up along the c-file, to counter-attack and/or do something to divert white’s assaulting pieces.

By move 23, white is in the process of simplifying their position. Simplifying in the end game, when I have an advantage in material is very important (the magic word, according to IC). “When [I am] a pawn ahead, reduce the material (and [my] opponent’s chances) by exchanging pieces, if it does not weaken [my] position”. (pg. 108)

Question: when should I break up my pawn structure around the castled king?

IC’s answer on page 109: the both sides need to give their kings escape squares (move f2, g2, h2 and/or f7, g7, h7). Moreover, “the break-up of the pawn position around the castled king is of now consequence in the ending. It is in the opening and middle-game that these moves endanger the health of the king, as then [they] may be assaulted by every piece on the board”.

Are perpetual checks now called stalemates or draws? Perpetual checks are addressed on pages 32, 348, and 355 of the 4th edition of the U.S. Chess Federation’s Official Rules Of Chess. KcKay Chess Library. Edited by Bill Goichberg, Carol Jarecki, Ira Lee Riddle. 1993.

USCF Rule 14C1. No “repetition of moves” or “perpetual check” draw. There’s no rule regarding a draw by repetition of moves. The draw is based on the repetition of position. The three positions need not be consecutive, and the intervening moves do not matter. There is also no rule regarding “perpetual check.”. It is irrelevant whether the claimant of [USCF Rule] 14C is delivering check.

USCF Rule 14C. Triple occurrence of position. The game is drawn upon a claim by the player… Yep, it’s a draw (page 32, 1993).

Special FIDE rules. The Drawn Game. FIDE Rule 12. A game may also be drawn, but only before the claimant’s flag falls, and supported where necessary by a completed core sheet… 12a. If a player demonstrates a perpetual check or a forced repetition of position (if this claim is found to be false, [their] opponent is compensated by having 2 minutes extra time added)… (pg. 348, 1993).

FIDE Rule 15. The game is drawn… [15d] by perpetual check, repetition of position, and “dead” positions. To claim a draw, a 4-time repetition is necessary with the players counting the moves out loud. The claimant must stop the clock after the 4th repetition (pg. 355, 1993).

USCF’s rule book also includes a chapter on 10 tips to winning more chess games, by IGM Arthur Bisguier. IGM Bisguier reminds the reader that there’s 3 stages of well-played chess:

- The opening. Players bring out their forces in preparation for combat.

- The middle-game. Players attack and counterattack.

- The endgame. There’s fewer pawns and pieces on the board, and it’s safer for the kings to come out and join the final battle.

IGM Bisguier’s tips echo all that I learned from Chess For Dummies (1996), Best Lessons Of A Chess Coach (1993), Chessbase — the Basics Of Chess (WinOS DVD), Logical Chess Move By Move (2004), and The Ideas Behind The Chess Openings (1989):

- Look at [my] opponent’s move.

- Make the best possible move.

- Have a plan.

- Know what the pieces are worth.

- Develop quickly and well.

- Control the centre.

- Keep [my] king safe.

- Know when to trade pieces.

- Think about the endgame.

- Always be alert. Pages 266 to 287. Includes a simple glossary!

Each of these big-assed books has their own tips for the novice and intermediate player. I’ll focus on IC’s book first, then revisit them.

- MCO-15. Modern Chess Openings. 15th edition. 2008. Nick de Firmian.

- The Middlegame in Chess. 1952. 1980. 2003. Reubin Fine, revised by Burt Hochberg. Chapter 14, pg. 389?

- Basic Chess Endings. 1941. 1969. 2003. Reubin Fine, revised by Pal Benko. Foreword by Yuri Averbakh. Chapter X (10), pg. 586?

Game 18.

This 1931 game was played in the Netherlands. White was played by Daniel Noteboom (Noordwijk, Holland, 1910-1932) and black by Gerrit van Doesburgh (1900-1966, Dutch Chess Championship silver medal in 1936). Again, black chose NOT to use the freeing move …c5 and it lead to king-side collapse.

So, what the hell IS the Queen’s Gambit… declined and accepted. According to MCO-15, the Queen’s gambit is 1 d4 d5 then 2 c4… How black responds to move 2 dictates whether the gambit’s accepted or declined. Queen’s pawn games are more about building pressure and then clashing mid-game. King’s pawn games are open fights right away (page 389, 2008).

According to IC, 4 Bg5 Nbd7 is a good play by black. I’d normally play 4… Nbc6 as it allows me to activate my black Queen’s bishop (and the Queen itself). I’d be cautioned against that as it ignores the threat of c5 and c6 — the dreaded c-file that seems to be whispered whenever one talks about Queen’s pawn openings. IC would advise me to advance my black c7 pawn to c5. “[Black’s] c-pawn must be free to advance and attack White’s centre” (pg. 112).

What does it mean when “a capture is forced”? According to “Chess For Dummies”, chess masters can predict several (or 1[yyyeah-boy]) move ahead. It’s all about pattern recognition. The author comments that that the same moves happen repeatedly — the moves are of a forced nature. So, one can learn to recognize patterns. As I practice, I can recognize more and more patterns in games — like mating patterns. When I’m ready, I’ll return to the 534-some-odd combinations puzzle book, Winning Tactics For Juniors, edited in 1984 by Lou Hays. Mr. Hays calls this work tactic training (pattern recognizing and solving).

Game 19.

This 1915 game in Vienna, Austria was another example of the black declined to challenge the centre squares and lead to sealing in Black’s c-pawn. White proceeded to swing the play from the Queen-side to the King-side.

March 26, 2025. Game 19. GM Ernst Grünfeld (white) versus Joachim Schenkein (black). It was played in Vienna (Austria-Germany) in 1915. 1-0.

Alright, let’s try this chess playing with a new set-up. My desk, DOT-mint, printer, scanner, X-box and gaming chair are in the study. Where can I play chess and enjoy the sunlight, without being cooped up in the small room?

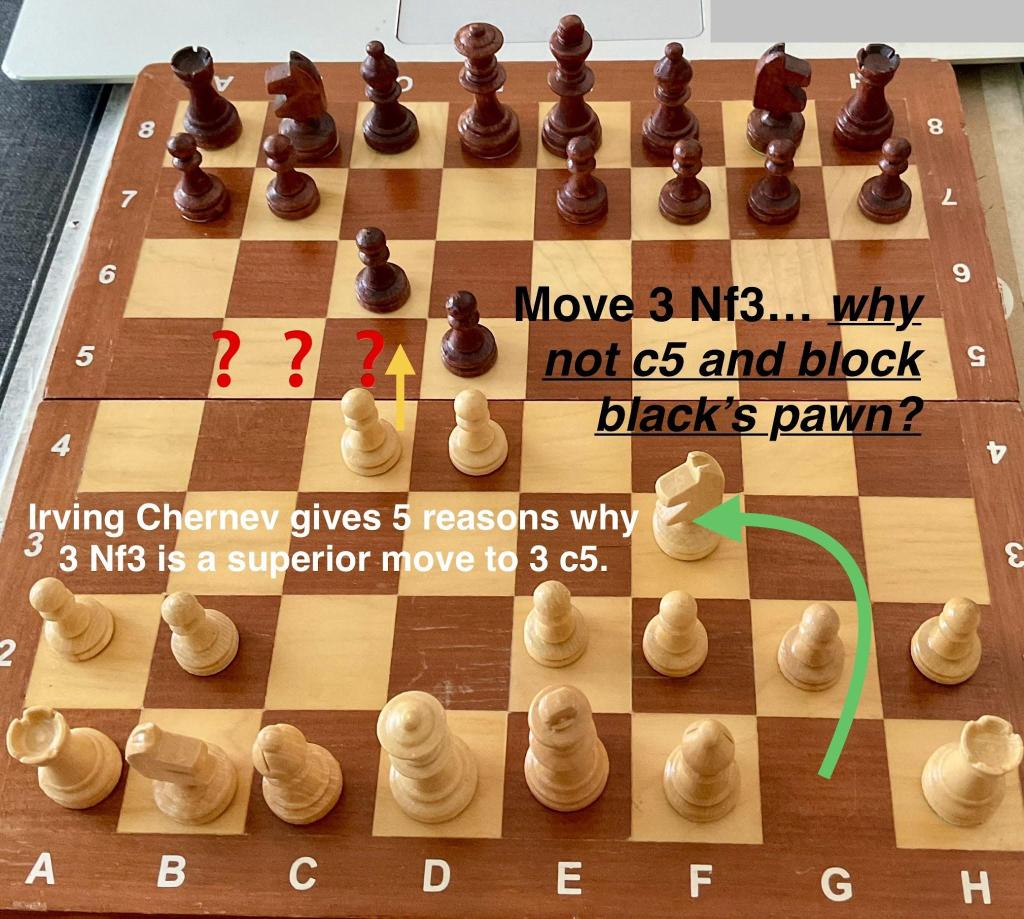

During move #3, white decides to play 3 Nf3 instead of 3 c5. Why is that? Doesn’t IC recommend I attack and keep attacking the centre squares? Here’s what I understand: this is the Queen’s pawn opening (1 d4) — and it has different strategies than the King’s pawn opening (1 e4). Queen’s pawn openings are all about applying tension to the centre squares — and that doesn’t require physical pieces inhabiting d4, d5, e4, and e5. I should also remind myself that pawns can only move 1 direction. So I should set them up and then develop other pieces (remember, players tend to call pawns… well pawns and pieces as all the rest [it’s jargon of the chess in-crowd]).

IC gave 5 reasons why (3 Nd3) > (3 c5):

- (i) “It’s a good strategy to maintain tension in the centre — to keep the pawn position fluid, not static.

- (ii) In advancing to c5, white gives up [their] attack on the enemy centre, and the option of exchanging pawns when it is worthwhile to do so. Such an exchange might be the means of demolishing Black’s whole centre!

- (iii) The c5-square should be an outpost for a piece, not a pawn. A piece posted there exerts a tremendous effect on Black’s whole queen-side.

- (iv) Placing a pawn at c5 closes the c-file and makes it useless for the operations of the queen or the rooks.

- (v) In the opening, pieces, not pawns, should be moved”. (pg. 119).

I still don’t buy IC’s explanation why chess-masters instinctively find the best moves… or that s/he are not looking too far ahead in a game… that they know the “right” move (oh fuck, I hate that saying)… Chess-masters dismiss offensive move choices, or choices that are distasteful to positional judgment.

There’s the phrase “positional judgment” and “positional play” again. What in Sam hell is that phrase? Deep breath = it seems there’s (at least?) 2 play-styles in chess: tactical chess and positional chess. Tactical play. Positional play.

Here’s a May 22 2020 article about it: https://www.chess.com/blog/FatherSmurf/ positional-vs-tactical-play-which-to-choose. Author: Richard Liu. The Blue Papa’s Blog. USA. https://www.chess.com/blog/FatherSmurf. Accessed March 26 2025 @ 17:45. There’s a picture of a knight with the caption, the night the most positional piece [on the board].

Tactical play-style: I’m looking for errors, blunders in my opponent’s moves. React.

Positional play-style: a war of attrition rather than deadly combinations.

A balanced player uses BOTH play-styles.

How can I play positionally? The positional game is commonly taught with strategies. In the opening, [I] move [my] pawns to the centre, [I] develop your[my]pieces, [I] get [my] king safe, etc. In the middle-game, [I] tend to focus on pawn breaks, open files, open diagonals, holes, etc. The endgame, [the blogger] would argue, would require the most positional skill. The endgame is typically less tactic-heavy since there are lesser pieces to consider on the board. When we have king-pawn endings, [I] have to outplay [my] opponent by having a better and faster strategy. These are all elements of good positional play and are ubiquitous in essentially all games (May 22 2020, Liu).

Back to the game. By move 11, white has positional advantage on the board, despite only having the same number of captured pieces and pawns as black. IC observes white has the following advantages:

- (i) [white’s] bishops have a great range of attack.

- (ii) [white] dominates the centre with [their] pawns.

- (iii) [white] controls the strategically important e5-square.

- (iv) [white’s] major pieces can operate with great effect on the centre files. (pg. 121).

By 14 Rd1 0-0, white has firmly established positional superiority on the board. I suspect pro-black (Black Is OK) author Andras Adjorjian would be critical of black’s cramped defensive game. IC summarizes white’s positional advantages:

- (i) his pawn position in the centre, restraining the free movements of the enemy pieces, is definitely superior to Black’s.

- (ii) his queen attacks 9 squares while black’s limited to 5.

- (iii) his bishops control 13 squares, whereas black’s are limited to 7.

- (iv) his knight enjoys wonderful mobility, while black’s knight can only retreat.

IC proceeds to crow about how white now has the right to look for decisive attacking combinations (I suspect this is why 21st century chess authors annotate games from over 50 years ago — the players are dead & the estates don’t care whether the players are criticized or not! IC seems to enjoy talking smack about past grand-masters).

Game 20.

Book report continues — March 27th. Game 20 was played by Akiba Rubinstein against Gersz Salwe in 1908 Poland.

By move 6, Rubinstein chose to move his king-side g2 pawn. And then IC claims that it’s a great move. He contradicts his earlier view of maintaining pawn-structure about the king. Unless white is going to 0-0-0, (queen-side castle), this is NOT a move I’d consider.

IC posits the queen’s pawn opening as a more cautious playing style. ~140 years ago, 1 e4 would have been THE opening move for white. It led to an attacking game. Bobby Fischer would disagree — and that’s why he became a flaming hot terror on the chess circuit (he was an aggressive player, no?).

By move 6, Rubinstein chose to move his king-side g2 pawn. And then IC claims that it’s a great move. He contradicts his earlier view of maintaining pawn-structure about the king. Unless white is going to 0-0-0, (queen-side castle), this is NOT a move I’d consider.

Isolated pawns can be viewed as negative OR positive. IC noted that there are arguments for both points of view.

PRO-isolated pawns =

- a spearhead for attacking entrenched positions; isolated pawns can have open files and diagonals hidden behind them that pieces can use for attacks.

- Move a pawn up to its side and its blocking power gets magnified.

- Isolated pawns can become passed pawns and thus be moved for promotion.

IC emphasizes repeatedly how important the c-file is… and space c5 in particular… in the Queen’s gambit. He also believes that once one starts the Queen’s gambit, it can’t be allowed to collapse. It’s the only way to explain why IC prefers 12 Be3, instead of (what I think) is the better Bf4 or Bg5. According to IC, the only way for black to foil white’s play is to prioritize disputing the centre squares and control c5 over castling. 0-0 is a good decision, however, it’s premature — it’s not the best move (as the fancy fuckers would say).

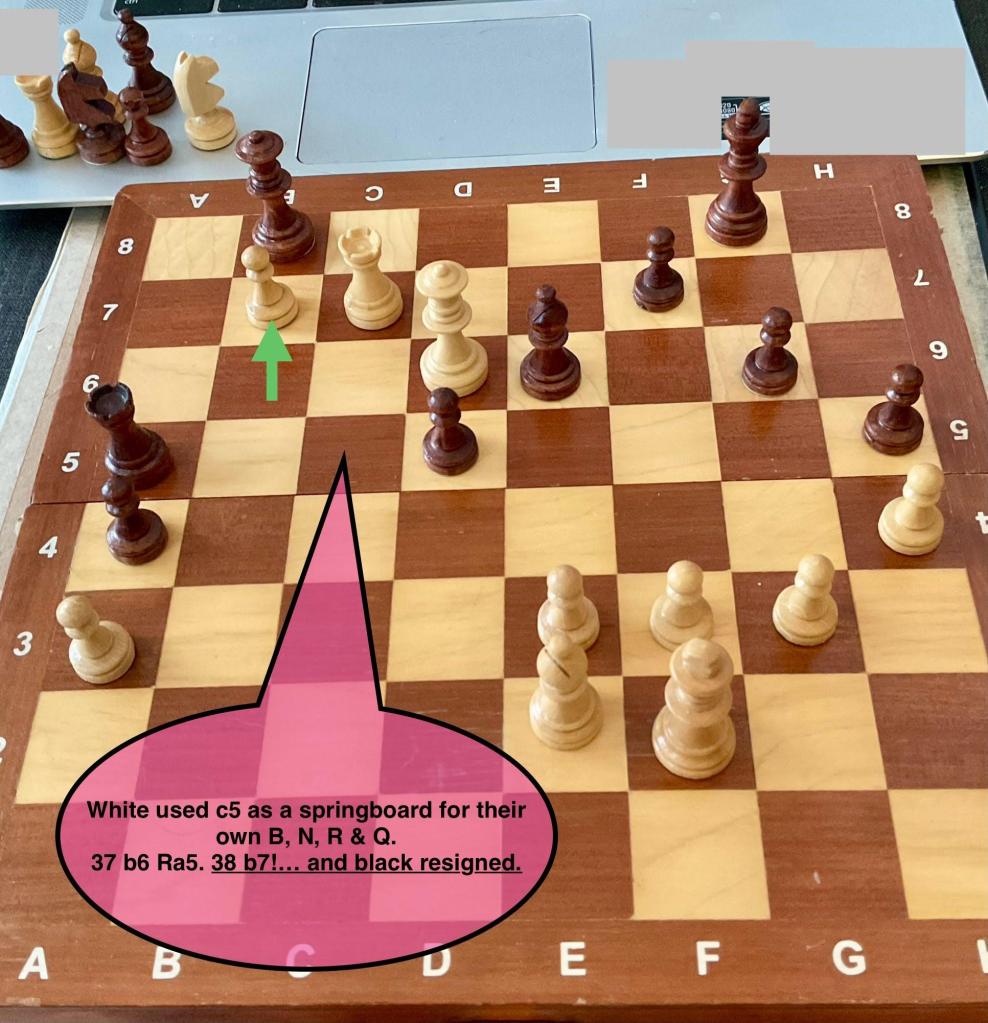

IC insists that “the whole game [was] a remarkable example of the systematic exploitation of a positional advantage. The manner in which the c5-square [was] used as a springboard for whites’ pieces — the bishop, knight, rook[,] and then the queen occupying it in turn — contributes a bit of sleight of hand to an artistic achievement of the highest sort”. (pg. 134)

Game 21.

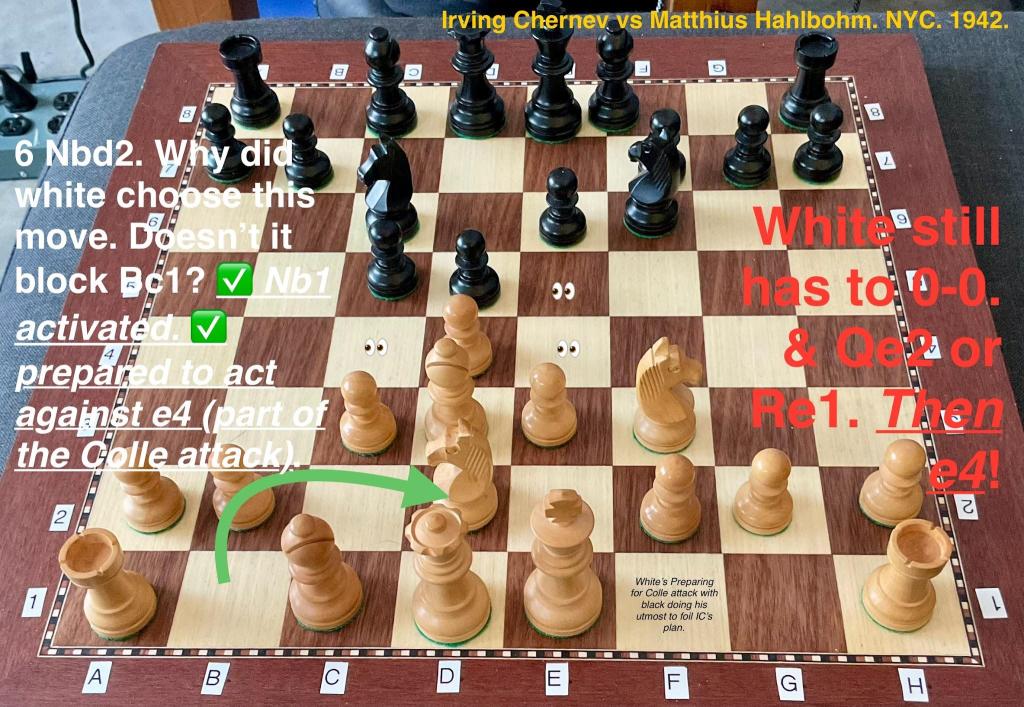

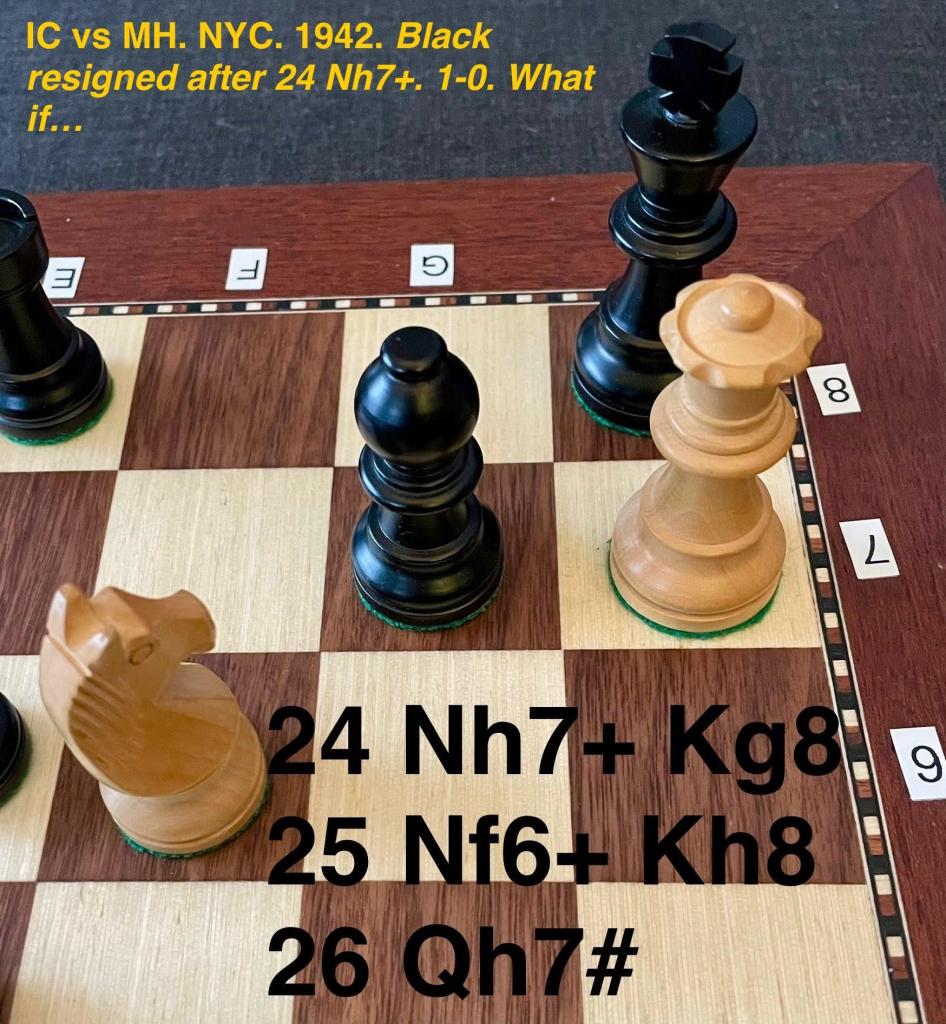

Irving Chernev (IC) versus Matthius Halbohm (MH). Our author played this game in 1942 New York. IC explains the Colle System in his annotated game. In the unit’s introduction (pp. 100-101), IC introduced this game as an example of black starting a strong counterattack against white. IC noted that black knight at d5 was under-supported. IC was able to make up for lost time with attacks on black. He also notes the game’s change in tempo.

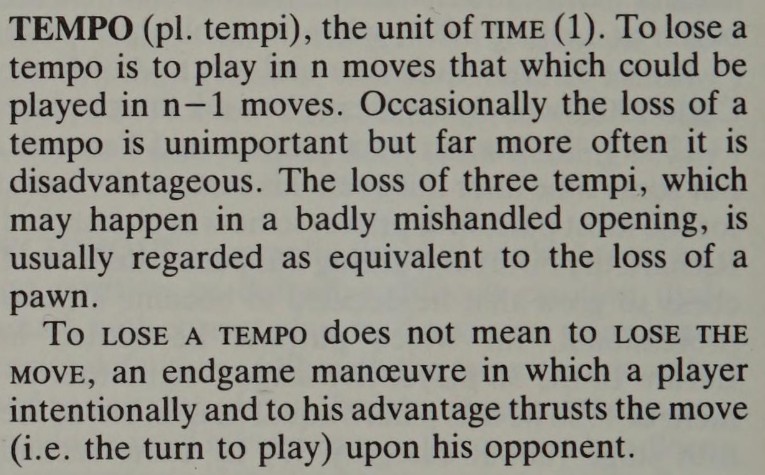

What is it with IC’s obsession with TIME and TEMPO?? I have to hit my 1996 James Eade reference (Chess For Dummies. [ISBN 0 7645 5003 9]). Tempo is derived from the Latin word for timed chess. It has a measurement, 1 tempi. James Eade defines the loss of 3 tempi as the loss of 1 pawn . To keep games lively, time limits are often used in games, so timed chess is defined as players must move X number of moves by Y time. If they run out of time, the player loses the game. (1996, pg. 342-343) I dug into the 1984 edition of

The Oxford Companion of Chess and found this TEMPO entry. My interpretation: unless I turn on the clocks on my computer games, I can ignore this feature. Hell, I can even ignore time limits with F2F games — I just can’t waste my opponent’s time agonizing each move.

So, what is the Colle System (or Colle attack)? Is it a white-only scheme? What can black do to foil it and counter-attack? In MCO-15, it’s outlined on page 506. According to IC, provided one sets the board up properly, white activates it with the move e4. PREREQUISITES: white must complete the following before triggering the Colle attack (with e4):

- (i) develop white’s f1-bishop at d3. It reinforces the pressure on the vital e4-square and attacks Black’s h-pawn, a tender point after [Black?] castles.

- (ii) post white’s queen’s knight (QN) to d2. This is DIFFERENT from QNc3 — don’t block white’s c-pawn (c2?). The knight at Nd2 will bear down on the e4 square and support the e-pawn when it reaches that square.

- (iii) King-side castle, 0-0, so that white’s h1 rook gets activated.

- (iv) Options: develop white’s queen to Qe2 AND/OR Re1. These moves prepare the pawn push.

- (v) advance the pawn to e4. “The pawn moves only 1 square, but it sets all the machinery in motion…” (pg. 135).

What can black do about it? Apparently, quite a bit! When black detects the above preparations , Black needs to dispute the important squares (0-0 [I’m guessing black doesn’t just copy-cat white’s moves], Qe2 and/or Re1, QNd2, Bd3). And fight for an equal share of the centre. According to IC, black needs to keep her knights controlling the centre. Black resists the urge to push a pawn to occupy …c4 thus stymieing white’s desire to develop white’s f1-bishop to d3. Apparently, black pawn to c4 relaxes pressure on white’s d4 pawn & the centre squares. IC wants back to defend herself against the Colle attack using the following tactics:

- Keep the black pawn’s position in the centre fluid.

- Black maintains pressure on white’s d-pawn in the centre.

- Black retains the option of exchanging pawns in the centre.

IC’s preparation for the Colle attack is not completely logical. I don’t understand why IC did that “in between move” 9 dxc5 with black (obviously having to)… Bxc5. He went on about losing a pawn. It’s his own game he’s self-annotating so who knows what he justified to himself! Meh, move on.

Meh and Murf. I’m back at it. Continued… Irving Chernev’s Colle attack is now underway. How should black respond? After a lot of what-ifs for 10… dxe4 & 10… d4 and the author spewing forth several lines of algebraic code (most ending with + or #), IC agrees with black’s ultimate decision: e5!! Black keeps pressure on the centre squares. So, 10 e4 e5 is the best counter-attack against white… and let the piece exchange begin.

The game continued another 14 moves before Black resigned. MH played a smart game against the author back in 1942. They must have both been very young men when this game happened.

Game 22? Nah.

Game 23.

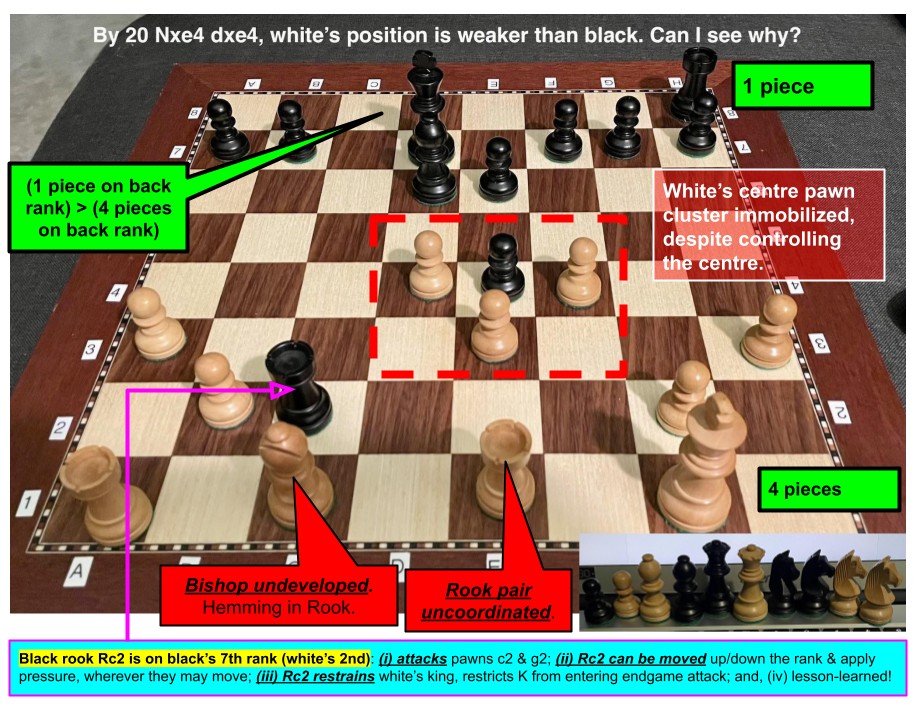

Game 23 will be an example of black winning using the Queen’s pawn opening (and its associated gambit). According to Irving Chernev’s unit’s introduction on page 101:

- It’ll be black, not white, that wrests control of the c-file. Look for Black’s counterattacks, like …c5.

- Look for a black rook invasion on the 7th rank.

- There’s also a black knight at e4.

- Black will double his rooks on the c-file.

- Black king messing around white’s pawns?!

- Black will be ahead in captured white pieces in the endgame. Look for black simplifying their play. The art of chess piece simplification.

In 1907, Dutch GM Louis Van Vliet played against Russian Eugene Znosko-Borovsky in Ostend, Belgium. And this time, I’m trying to keep track of the game from Black’s point of view!

The Stonewall Variation. The Stonewall Attack. According to MCO-15, this is part of the Dutch attack, popular among some hyper-modern players. IC has odd opinions about it. He detests it! I’m seeing IC’s bias. He thinks white is moving too many pawns at the beginning of the game. By the 5th turn, 4 of 5 moves have been minor pieces and he thinks that violates sound strategy.

This game’s a bit of a mystery to me. White captured a queen, a knight, and a pawn. Black’s captured a queen, a bishop and a pawn. Bishops are worth some what more than knights in a strict sense.

Ahhhh. Forget it. This game was too hard to follow using pieces. I’m trying to view it from black’s point of view and it’s screwing me up.

Book report, Next day — I’m trying again. By move 19, white and black have been exchanging major pieces. Both queens are off the table. White’s lost a bishop and a knight. Black’s lost both knights. Each side lost a pawn. And yet, IC is still maintaining that black has positional advantage with white madly trying to clear the board to gain mobility. 19 Nd2 Kd7. IC notes that quick mating isn’t as high of a risk. So now it’s time for black to activate his king. Black’s king doesn’t have to hide behind its pawns and its attacking power can now be enabled. Wait… king’s attacking power?! “19… Kd7. much more energetic than castling. Mating threats are not likely with so few pieces on the board, hence the king comes out into the open. The king’s power increases with every reduction of force, and as befits a fighting piece, the king heads for the centre to assist in the attack.” (pg. 153) I find it hard to get my head around having an attacking king. Surely it needs accompanying pieces as its bodyguards!

IC has the following lesson about moving one’s rooks about the board:

- (i) In the opening, shift the rooks to the centre, on files likely to be opened.

- (ii) in the middle-game, seize the open files and command them with my rooks.

- (iii) in the endgame, post my rooks on the 7th rank [of my opponent]. Doubled rooks on the 7th ranks are almost irresistible in mating attacks. If there is little material left on the board, the 7th rank is a convenient means of manoeuvring a rook behind the enemy pawns.

When kings move away from their pawn shields and engage the enemy, they be powerful pieces. Kings can attack loose pawns and lead their own pawns to get promoted. Obviously, kings are not moved until the endgame. In game #23, the fight got ugly with white resigning by move 36. 0-1.

the chessmaster explains his ideas. page 157.

Book games #24 to 33. I don’t see the value of decoding these games. They’re reinforcement and I want to practice on my own. This unit allowed IC to provide additional commentary that repeats what was outlined above. I’m going to leave it alone. No thanks. I’m ending my IC-specific notes. The end.

index of openings. page 256.

I need to go to other books about openings. Why does one study them? What happens when one strays from such patterns? Irving Chernev identified the following openings in his book:

| Opening | Beware: basic information skimmed from Wikipedia! |

|---|---|

| Colle System | Popularized in 1920s, for white. Colle-Koltanowski System. ECO (Encyclopedia of Chess Openings) D05. Parent = Queen’s Pawn Game, closed game. White’s opening Pattern: d4, Nf3, e3, Bd3, c3. |

| English Opening | 19th century master Howard Staunton. ECO A10. It can transpose into all kinds of variations. Parent = King’s Pawn Opening. Pattern: Whenever white opens with 1 c4. |

| French Defence | It gained popularity during a 1834-36 London vs Paris correspondence match. ECO C00. Parent = King’s Pawn game, open. Pattern: 1 e4 e6. |

| Giuoco Piano | Popularized in the 16th century. Italian Game. Piano Opening. Parent = King’s Pawn Opening, open. ECO C50. Pattern: 1 e4 e5. 2 Nf3 Nc6. 3 Bc4 Bc5. |

| King’s Gambit DECLINED | Apparently, it’s one of the oldest document openings & was kicking around Europe in 1497! Uses the ‘best by test’ 1st move, e4. Parent = King’s Pawn Opening, open game. Black ignores white’s pawn offering. ECO C30. Pattern: 1 e4 e5. 2 f4 …NOT exf4. |

| Nimzo-Indian Defence | Wikipedia claims it’s a hyper-modern opening, popularized in 1883 London matches. Named after a dude named Aron Nimzowitsch? Parent = Queen’s Pawn Opening. ECO E20. Pattern: 1 d4 Nf6. 2 c4 e6. 3 Nc3 Bb4. |

| Queen’s Gambit ACCEPTED | QGA. Popularized at the 1866 World Chess Championship. Parent = Queen’s Pawn Opening. ECO D20. Pattern: 1 d4 d5. 2 c4 dxc4. |

| Queen’s Gambit DECLINED | QGD. Parent = Queen’s Pawn Opening. ECO 30. Black ignores white’s c4 pawn. Pattern: 1d4 d5. 2 c4 e6. |

| Queen’s Indian Defence | QID. Parent = Queen’s Pawn Opening, Indian Defence. ECO E12. Pattern: 1d4 Nf6. 2 c4 e6. 3 Nf3 b6. |

| Ruy Lopez | Supposedly named after a 16th century Spanish priest, Ruy Lopez de Segura. It might have been documented in a 1490 Gottingen manuscript? ECO C60. Parent = King’s pawn opening, King’s night opening, Spanish opening, Spanish torture (slang). Pattern: 1 e4 e5. 2 Nf3 Nc6. 3 Bb5… and then all hell breaks loose! |

| Scandinavian Defence | Centre Counter Game. Centre Counter Defence. This is an old one! It developed in Valencia in 1475 as part of a fictional game between 2 characters! Black forces white to play an open game. Parent = King’s pawn game. ECO B01. Pattern: 1 e4 d5. |

| Sicilian Defence | It was popularized in 1594 by Giulio Cesare Polerio & Gioachino Greco. Parent = King’s pawn opening. ECO B20. Pattern: 1 e4 c5… and then all hell breaks loose. |

| Stonewall Attack | The stonewall setup. The Dutch Defence. Bird’s Opening. IC had issues and bias against this pattern (he complained that it violated the spirit of chess and ignored opening game norms)! Take a look at how many pawns the player activates! The first documented game was in 1842 London. Parent = Queen’s pawn game. Stonewall Attacks are considered a chess system, with a specific pawn formation. ECO D00, A03, A45. It can be set up by both white or black! Wikipedia notes its inherent weaknesses: inflexible pawn structure, weak light-square presence, underutilized Bc1 (or in black’s case, Bf8 or Bc8). Pattern: d4, e3, Bd3, Nbd2, f4(?), Ngf3, c3(?). |

| Opening | Basic information |

book cover art.

I used the following URL links, that are valid as of April 10 2025:

Link to article about chess combinations.

https://www.chess.com/ article/view/ zwischenzug-chess

https://idioms.thefreedictionary.com /be+in+a+ right+pickle

https://www.chess.com/blog/FatherSmurf/ positional-vs-tactical-play-which-to-choose